KELCEY ERVICK is the author and illustrator of the graphic memoir, The Keeper (Avery Books/Penguin 2022), and co-editor, with Tom Hart, of The Field Guide to Graphic Literature (Rose Metal Press 2023). Her three previous award-winning books of fiction and nonfiction are The Bitter Life of Božena Němcová, Liliane’s Balcony, and For Sale by Owner. Her stories, essays, and comics have appeared in the Washington Post, The Rumpus, The Believer, Lit Hub, and elsewhere. She has received grants from the Indiana Arts Commission, the Sustainable Arts Foundation, and New Frontiers in Arts and Humanities at Indiana University. She has a Ph.D. from the University of Cincinnati and is a professor of English and creative writing at Indiana University South Bend.

KELCEY ERVICK is the author and illustrator of the graphic memoir, The Keeper (Avery Books/Penguin 2022), and co-editor, with Tom Hart, of The Field Guide to Graphic Literature (Rose Metal Press 2023). Her three previous award-winning books of fiction and nonfiction are The Bitter Life of Božena Němcová, Liliane’s Balcony, and For Sale by Owner. Her stories, essays, and comics have appeared in the Washington Post, The Rumpus, The Believer, Lit Hub, and elsewhere. She has received grants from the Indiana Arts Commission, the Sustainable Arts Foundation, and New Frontiers in Arts and Humanities at Indiana University. She has a Ph.D. from the University of Cincinnati and is a professor of English and creative writing at Indiana University South Bend.

Q&A with Kelcey Ervick

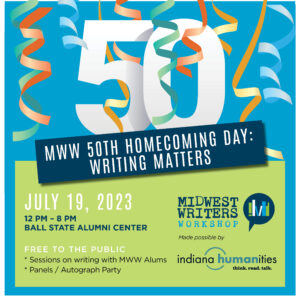

Kelcey Ervick is a creative whirlwind and a pleasure to know. She’s inspired me to try out my hand with some drawing*, and I certainly hope you’ll try it too, after reading this interview–then sign up for more of her wisdom and insight in her sessions at MWW23!

MWW: I love the way you blend images and illustrations with words. Have you always told stories that way? Was it a sort of “eureka” moment or a more gradual intertwining?

KE: One eureka moment I had was reading Maira Kalman’s 2007 book, Principles of Uncertainty, filled with her gouache paintings of everything from an extinct dodo bird to Louise Bourgeois’ bathroom and lettered by hand in her whimsical writing. I’d recently gotten my PhD in English and it was a revelation: the images, the handlettering, the playful prose. I remember thinking, “You can do this?” Soon after, I read Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, which is a haunting personal and literary story of her father’s death told through comics, and I had the same thought, “You can do this?” My visual storytelling is hugely influenced by the openness of Maira Kalman’s pages and the layered, literary narrative of Alison Bechdel’s books.

MWW: How does the incorporation of images enhance or underscore the themes or aboutness of a work?

KE: Visual elements such as color palette, lines (weight, straightness, etc), and visual style (realistic, expressive, etc.) do so much work to underscore the subject matter and themes. You know at a glance if the work is serious and powerful like Kristen Radtke’s precise and sophisticated digital illustrations in Seek You: A Journey through American Loneliness; or filled with personal, humorous social commentary like Mira Jacob’s collage/zine-style in Good Talk,; or brimming with characters and community in the lively ink lines of Ebony Flowers’ Hot Comb.

I also love how images can take on metaphorical meanings and become a visual motif. In my graphic memoir The Keeper, I write about my club soccer team that I played on the 1980s, the Cardinals (named for Ohio’s state bird). Throughout the book I used the language and imagery of cardinals—in flocks, as homebodies, in flight—to reflect the book’s themes of friendship, loneliness, and finding my own path.

MWW: What is a common misconception people have about graphic novels and writing with images that isn’t so?

KE: There are lots, but I’ll address two of them:

That it’s not serious writing. It’s what I thought too before I read Fun Home and Persepolis and Maus. Graphic novels are made in the same medium as newspaper cartoons and there’s an association with lightness and comedy (the “funnies”). Plus there are pictures, which people associate with children’s books, so they seem dumbed down or for kids. I remember reading Fun Home and thinking, you can talk about Virginia Woolf in a comic?

The other misconception people often have is that they can’t draw and therefore they can’t make comics. But I get my students, who have very little experience drawing, to make the most beautiful, hilarious, thoughtful, and introspective comics. Readers just need to know what it is you’re drawing. Draw a car, a house, a bird. Ask someone if they can identify what you drew. Yes? Great. Start making a comic!

KE: It’s odd to me that I hadn’t fully made the connection before writing The Keeper, but I came to see how clearly the daily habit and mental training of being an athlete informed my approach to being a writer. Every day after school, whether I felt like it or not, I changed into practice clothes—shorts, t-shirt, cleats, hightops, shinguards, goalie gloves, softball glove, and don’t forget a ponytail!—and went off to practice soccer, basketball, or softball. We ran plays, scrimmaged one another, worked on ball-handling and batting and shooting and passing. Some days I put on a uniform and played a game, testing out what we’d practiced in front of crowds and with referees and buzzers. We won games, we lost games. We pushed ourselves to work harder, dig deeper, do better. I played on different sports, with different teammates, and different levels of success.In 2018, when I really wanted to get better and make visual storytelling central to work, I knew what I needed to do: I had to practice it every day. And that’s what I did. Each day I got out some paints and paper, got a jar of water, put on a smock, and painted something. Every day. My creative life and my storytelling have never been the same. I could have never written and illustrated The Keeper if I hadn’t done it.

The Keeper itself is also so much about being a goalkeeper, and how similar it is to being a writer: you’re alone a lot, you’re apart from the team but also a part of it. It’s a position of high highs, low lows, and long in-betweens. A goalkeeper can be the hero or the zero. I had to learn not to blame myself for goals, which is similar to not taking rejection too personally as a writer. It stings, it sucks, but it’s not necessarily my fault. And if it is, I need to do better. Back to the practice gear, the reps, the preparation.

MWW: Your turn! What question do you wish that someone would ask you about writing, but nobody has? Write it out and answer it!

KE: How has blogging shaped your writing?

Before I made the shift to visual storytelling, I was a fiction writer trying to learn how to write nonfiction, which specifically meant trying to find my voice when it wasn’t hidden behind a fictional narrator and fictional situation. When it was just me writing about my boring old life and thoughts. Then, in 2010, I started a blog, PhD in Creative Writing. I had very few subscribers, so it felt like a secret. I was free to write whatever interested me, and in doing so I “found my voice.”

But I didn’t want the blog to be only about me, I wanted it to be a resource for others, so I from 2011-2015 I ran a bi-weekly interview series, “How to Become a Writer,” where writers answered the same 5 questions about their journey. I interviewed people I knew, but I also “met” a lot of other writers through recommendations, and it expanded my community in wonderful ways.

In 2022, for better or worse, I made the decision to switch from WordPress to Substack, where I now have an illustrated newsletter, The Habit of Art, the title of which is inspired by my years of daily drawing, and where I write and draw about my creative journey, which I hope might be of use to others. I know it’s useful to me because the posts are like soccer practice: I learn through doing it regularly, through the process of coming up with an idea, finding the right words and images, cutting and adding, and interacting with readers.

They will help you write your story!