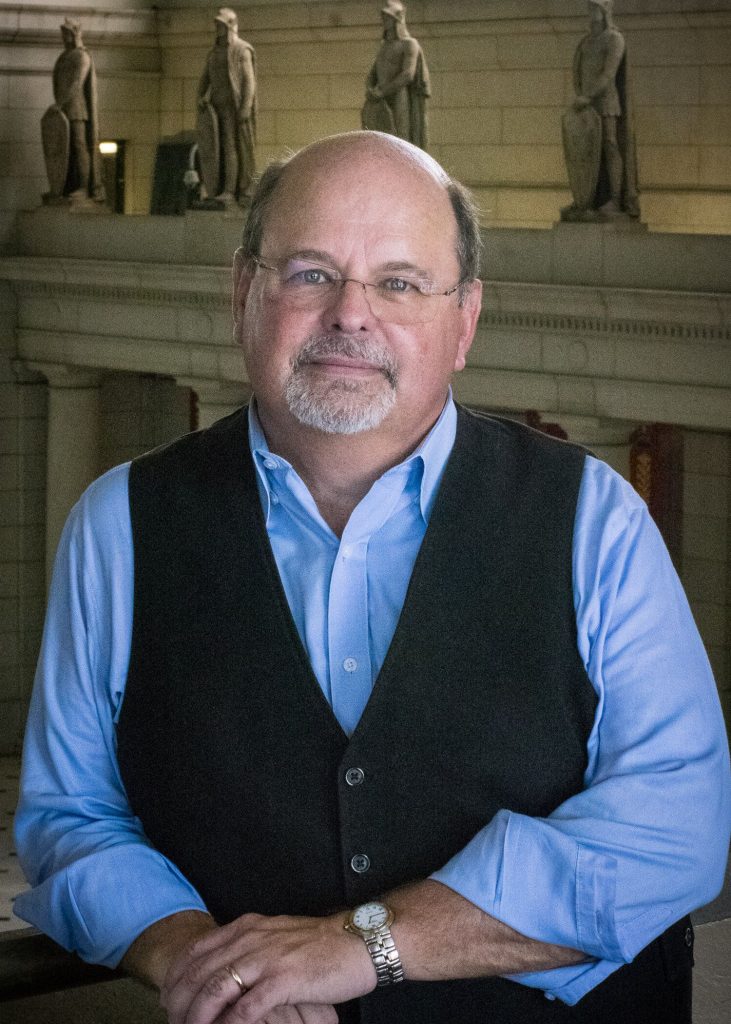

John Gilstrap is the Thriller Award-winning, New York Times bestselling author of over two dozen thrillers, including Harm’s Way, White Smoke, Deadly Game, Blue Fire, Stealth Attack, Crimson Phoenix, Hellfire, Total Mayhem, Scorpion Strike, Final Target, Friendly Fire, Nick of Time, Against All Enemies, End Game, Soft Targets, High Treason, Damage Control, Threat Warning, Hostage Zero, No Mercy, Nathan’s Run, At All Costs, Even Steven, Scott Free and Six Minutes to Freedom. Prior to the beginning of his writing career, John served 15 years in the fire and rescue service.

John Gilstrap is the Thriller Award-winning, New York Times bestselling author of over two dozen thrillers, including Harm’s Way, White Smoke, Deadly Game, Blue Fire, Stealth Attack, Crimson Phoenix, Hellfire, Total Mayhem, Scorpion Strike, Final Target, Friendly Fire, Nick of Time, Against All Enemies, End Game, Soft Targets, High Treason, Damage Control, Threat Warning, Hostage Zero, No Mercy, Nathan’s Run, At All Costs, Even Steven, Scott Free and Six Minutes to Freedom. Prior to the beginning of his writing career, John served 15 years in the fire and rescue service.

Four of John’s books have been purchased or optioned for the Big Screen. In addition, he has written four screenplays for Hollywood, adapting the works of Nelson DeMille, Norman McLean and Thomas Harris.

A frequent speaker at literary events, John also teaches seminars on suspense writing techniques at a wide variety of venues, from local libraries to The Smithsonian Institution. Outside of his writing life, John is a renowned safety expert with extensive knowledge of explosives, weapons systems, hazardous materials, and fire behavior. John lives in Shepherdstown, WV. Follow John on Twitter and Facebook, check out his YouTube Channel and website and subscribe to his e-newsletter mailing list!

John will teach the sessions “Adrenaline Rush: How to Write Suspense Fiction” and “Blood on the Page: Using Research to Create Credible Fiction.” He’ll also sit down with Matthew Clemens, Barbara Shoup and Angela Jackson-Brown for for the panel “The Stretch Run: from manuscript to book,” and he’s on the manuscript evaluation team.

John Gilstrap is no stranger to MWW, but every time we talk to him we learn a little bit more! He’s a renowned expert in his craft and specific genre, and has wisdom for all of us when it comes to how to approach the writing in our lives.

MWW: Your session on making quick work of research sounds like it will be helpful to those of us who get lost in the rabbit hole of available information. Tell me about a time when you got lost in the research. How did you pull yourself out?

JG: When I was a kid, I read the encyclopedia for fun. My parents had purchased one of those 20-volume sets that filled a whole shelf on our bookcase, and I would kill hours exploring topics that I didn’t even know existed. One book was allowed in the bathroom that my brother and I shared, and that was the Webster Collegiate Dictionary. Exploratory research is baked into my DNA. It’s fun for me.

That said, I’m keenly aware that work hours are work hours, and during that time, I keep my research focused on the slice of information I need for the scene that I’m writing. When I get the answer I’m looking for, I switch back to my manuscript and keep writing. I know it’s a boring answer, but the way to pull out of the rabbit hole is to not enter it until you have the time to enjoy the journey.

MWW: Writing about explosives and weapons is an easy one for writers to muddle, from terminology and realistic outcomes. What are some of the common mistakes you see writers make when it comes to writing about things that go “boom”?

JG: A good rule to live by is this: Everything they show on television and movies is wrong. Every. Thing. From the way cops and soldiers hold their weapons to the way SWAT teams stack up at the door. Cars don’t explode–ever, unless there’s a bomb inside. People don’t fly backward when they’re shot, and they don’t trampoline through the air when they’re blown up. Bombers don’t use red wires and green wires–they just use wires. No liquids burn; only gases and vapors burn. The list goes on and on.

MWW: Tell me about the most significant change you’ve ever made in a project? I’m talking big overhaul. What made you do it, and what changed in the project—and perhaps in you—as a result?

JG: My first novel, Nathan’s Run, was an international bestseller in 1996 and it launched my career, selling hundreds of thousands of copies around the world. It was also named as one of the 100 most banned books in America, due to foul language. The protagonist, Nathan Bailey, is twelve years old, and the story is about his escape from a juvenile detention center after a failed attempt to murder him. While I never intended the book to be read by young adults, the young adult market flocked to it.

Having spent many years in the fire & rescue service, my vocabulary can get pretty raw, and that was the narrative voice I brought to Nathan’s Run. It never occurred to me that people would be offended by the choice of words in a story, but I was wrong. Over the years, I received hundreds of letters and emails from people telling me that they love the story, but are disappointed that they couldn’t share it with friends and family members because of the offensive language.

So, when the rights reverted to me, and I resold them to Kensington Publishing, I embarked on what I call the Great Defuckification. I excised every one of the high-end bits of profanity. No one has ever complained that it wasn’t there. Since then, I’ve never included an F-bomb in a book.

MWW: Often times writers have a “do as I say, not as I do” approach to writing. What is some advice that you give in your classes that you wish you did more of in your own writing?

JG: I’m not sure this question applies to me. Every time I teach a course, I stress that writing is a free-form endeavor. There are no rules. None. What works for me might not work for anyone else, and what works for others most certainly won’t work for me. While I talk about the importance of outlining for some, I’m very clear that I personally do not outline. It’s a waste of time for me. I tell students that while the process of storytelling can be difficult at times, it should always be fun. If it’s not fun, then that will show in the prose.

MWW: Your turn! What question do you wish that someone would ask you about writing, but nobody has? Write it out and answer it!

JG: I can’t think of a question I’ve never been asked, but here’s an answer I wish people would pay more attention to: Think less and write more. Just spill words onto the page and enjoy playing with your imaginary friends. Don’t worry about making it good until you’ve told the story you want to see on the page. The act of writing is where all the learning occurs. If you’re in school, consider getting a degree in something other than writing. Get a job that exposes you to the most varied life experiences. The more you live, the more you see, the more fodder you have for your stories. Embrace the fact that your earliest efforts will not be very good. This is a craft, and that’s the way crafts are supposed to work. The more you practice, the more skilled you become.

And always be reading. Always, always, always be reading.

“Over the years, I’ve participated in more conferences than I can count, but time after time, Midwest Writers Workshop ranks among the best of the best. The students are anxious to learn, the faculty comes to teach, and the result is electrifying.” — John Gilstrap